I flew out for Puerto Rico at 4:00 PM on Sunday, changed planes in Atlanta, and got into San Juan just a little before ten. The tail end of tropical storm Ernesto was just passing by the island, and the tropical night was warm and rainy.

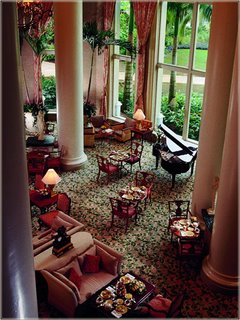

We were staying at the Ritz-Carlton, a massive ocean-front palace with a full casino and a spa lots of dark wood and marble in the lobby. So far so good. The problem was: I had an meeting the next morning at 7:30 am and, because of other commitments back home, a flight out at 2:30 PM that afternoon. All in all, just 17 hours on the ground, including sleep time. No time for sopa de arroz con pollo, no time for plantain tostones, and not even enough time for lechon asado (barbecued pig). Not even enough time to snap any pictures (I borrowed the one here from the Ritz Carlton website.)

At least I got a good mojito.

Okay, so it's really a Cuban drink, but the rum was Puerto Rican, and it was advertised as the specialty of the house at the Ritz-Carlton Lobby Lounge, where my colleagues and I had a drink and watched as the tropical rain pounded down outside. It seemed like the thing to try. And it was really, really good.

Mojitos are a big trendy drink in the U.S. now--so trendy that Delta airlines was flogging them onboard the plane on the trip down, made I'm sure from some high-fructose mix. Most mojitos I've had have been, frankly, pretty disappointing--a mess of soda water and undissolved sugar and annoying clumps of mint leaves. I've made them at home, too, but they've always come off as too strong--either too much of an alcohol bite from the rum or too sour from the lime.

So, when I took a sip of the one at the Ritz-Carlton and found it a perfect smooth blend of sweetness, sourness, and mint, I kept one eye on the bartender and took notice the few next times he made mojitos.

The ingredients were simple: rum, fresh lime juice, sugar, and mint with just a touch of soda (not half a glass of soda, as I've seen it made in too many places). And, smooth as it was, it wasn't because he skimped on the rum--the doses, in fact, were pretty darn generous. The key, it seems, was in the muddling. In most mojitos I've had, the mint is beat up a little in a cocktail shaker, sometimes with a spoon and sometimes with an actual wooden muddle. At the San Juan Ritz, the bartender used an actual mortar and pestle (both wooden, I think) to not just crush the mint leaves but to pulverize them. The resulting drink was not clear with little bits of green mint leaves floating around inside but rather a bright, neon-green liquid. Lots of little bits of mint were suspended in the liquid, but so tiny that they didn't stick to your tongue and clog up the works while you were drinking. It was so good that I wanted a second one, but I had to be up in five hours, so it was off to bed.

The only other island specialty I got to sample was the coffee, which is grown locally and brewed up thick and strong--more like an espresso than the typical weak mainland brew, and served in appropriately small cups. At our meeting that morning, most of the attendees took their coffee con leche, with a health dose of warm milk added and mixed in. A carafe full of milk was kept warming on one of the coffee-machine burners just for that purpose. I had mine black, and its strong, rich flavor helped kicked the morning into gear. Then it was a blur of meetings, high speed rides to the airport, and racing for the airplane gate.

With any luck, I'll be heading back to Puero Rico again in the near future, and next time I plan on staying at least long enough to eat dinner.