5205 Broad St.

Richmond, VA

http://www.extrabillys.com

View on Al Forno's Big Barbecue Map

View on Al Forno's Big Barbecue MapThere’s long been a knock against barbecue in Virginia. Though it was the historical birthplace of barbecue in America, the story goes, the tradition died out somewhere back in the 19th century and now is hard to find at all. Like most claims about barbecue, this one is likely to be disputed hotly by a group of partisans, and, if not exactly thriving, barbecue can at least be found in the state of Virginia. But is it really "Virginia Barbecue"?

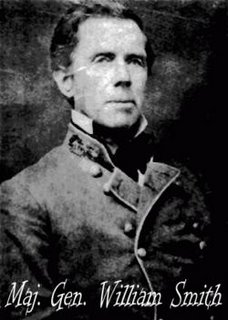

While in Richmond not long ago, I was taken by a group of locals to Extra Billy’s, a barbecue joint on West Broad St. The name itself is intriguing, suggesting a barbecue man with reputation for serving up large portions. But, as it turns out, William “Extra Billy” Smith was actually a noted Virginia politician and Civil War hero who served two terms as Governor (1846-1849 and 1864-1865). There are varying reports on the origin of the nickname “Extra Billy”. The restaurant’s menu claims he earned the name “because of the extra effort he always made for his constituents”, while other sources claim it was for “questionable perks” he received as a federal mail contractor in the 1820s.

Either way, it’s a good name, and one that has no apparent connection with the restaurant, which has only been around since 1985. But, the barbecue was pretty good. I had the lunch combo plate with pulled pork and sliced brisket—perfect to guarantee a sluggish afternoon—with slaw and potato salad. The side dishes were tasty but totally unnecessary since the two mounds of meat on the platter alone were more than I could finish.

The pork was pretty good—tender and slightly smoky—but the brisket was better, with just the right crispiness on the outside and a good quarter-inch pink smoke ring and the hickory flavor to match. The table had two bottles of barbecue sauce, one a spicy vinegar-based, the other a reddish, thicker blend. I preferred the latter, which my dining companions referred to as "Virginia style".

As it tends to do, the conversation drifted toward other barbecue restaurants and everyone’s favorite barbecue styles. And, as it turned out, not all of my lunch companions were native Virginians. One, a recent transplant from Memphis, waxed longingly about that city’s rib joints and declared them to be the only "real barbecue". Much to my surprise, the two Virginia natives did not come to their state’s defense. In fact, they left the field uncontested, with one admitting that he actually preferred Lexington, North Carolina style pork, and the other proclaiming that the sweet mustard-based sauce (which is found mostly in my neck of the woods in South Carolina) was his favorite.

And what was the deal with that brisket, anyway? It was good—don’t get me wrong—but smoked beef brisket is a hallmark of Texas barbecue, not Virginia. Ditto for the smoked sausage that is also on Extra Billy’s menu, described explicitly as “Texas rope sausage with mustard flavor,” and the red tomato-based sauce that I found such a good compliment to the brisket.

I think this is far more than just another isolated example of the geographic dissonance of fast-casual barbecue. In fact, I suspect the naysayers are indeed right and there really is no Virginia barbecue anymore.

The advertising for Virginia barbecue joints confirms that this once-proud barbecue state now has an inferiority complex. In their “story” on their website, Buz & Ned’s in Richmond, VA, claims to have explored and sampled every great barbecue joint across America, returning with 150-year old recipes and bringing traditional barbecue to Richmond, “a great city, but without a real BBQ tradition.” The Silver Pig Barbeque Restaurant in Lynchburg claims to have “the most authentic Carolina barbeque this side of the North Carolina state line.” Three L’il Pigs in Daleville (just North of Roanoke) boasts “the tastiest, slow-cooked, hickory-smoked North Carolina-style barbeque anywhere in the valley".

The menu for the Virginia BBQ Company in Ashland offers the Original Virginia BBQ Sandwich, which it claims is “Virginia’s traditional style, hand pulled pork, tossed in a flavorful homemade BBQ sauce.” But, the owners are either not very confident in their local product or are simply pragmatic about market demands for they also offer the Classic NC BBQ Sandwich (“Folks down in North Carolina would never put none of that red stuff on no BBQ”) and the Texas BBQ Beef Sandwich.

It wasn’t always this way. The colony of Virginia was the birthplace of barbecue, the soil where the seed was planted and from which it spread throughout the South and, eventually, clear out to the West Coast. By the mid 18th-century, outdoor barbecues had become one of the key social events in Old Dominion society. References to barbecues are sprinkled throughout the letters and diaries of this country's founding fathers, including George Washington himself, and visitors described the gatherings in travelogues as a remarkable phenomenon peculiar to the colony. As Virginians left their home state and migrated south westward through the Carolinas into Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama, they took their barbecue traditions with them, and it is common to see references in 19th century newspapers to "old-fashioned Virginia barbecues."

So what happened to make barbecue die out in its native state? That's a difficult question to answer. Thoughout the United States in the early-to-mid 20th Century, barbecue was making a transition from being served large-scale at free public gatherings to being a commercial product sold in individual portions at restaurants. In the 1920s and 1930s, Virginia had as many "good old fashioned" election and church-picnic barbecues as anywhere else.

Somehow, no legendary barbecue restaurants developed in Virginia that could rival the likes of Arthur Bryant's or Gates's in Kansas City, the Rendevouz in Memphis, or any of the two dozen joints in Lexington, North Carolina. These restaurants helped codify the style of barbecue unique to their regions and, in doing so, laid the groundwork for those regions' claims for being having the one "real barbecue".

People in Virginia still love to eat barbecue, they just don't seem to have much of a distinct local feeling for the dish.