Monday, December 25, 2006

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Lowcountry Nibbles

As Chuck Boyd has observed, several more of Charleston restaurants have gone 100% smoke free of their own volition.

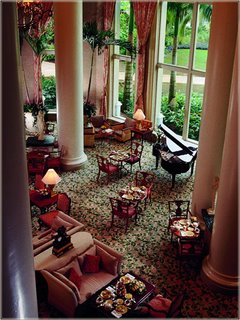

I'd seen quite a few articles about The Sanctuary on Kiawah, the Wentworth House downtown, and the Woodlands in Summerville getting five-diamond ratings from AAA. But now the stories appear to have gotten picked up as far away as Canada. Too much more press like this and Charleston may turn into a tourist destination.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Charleston Coffee Exchange

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Here's Your Sign

Monday, December 18, 2006

Holy Guacamole!

Like much of the prepared guacamole sold in supermarkets, Kraft guacamole is essentially a whipped paste made from partially hydrogenated soybean and coconut oils, corn syrup, whey and food starch. Yellow and blue dyes give it the green color.

Of course, no story is ever quite what it seems. As it turns out, the woman bringing suit against Kraft is a serial plaintiff in class-action lawsuit against corporations, and Kraft's "Guacamole dip" isn't even all that popular. But still--green-dyed whipped oil/sugar paste? Gargh.

And, Kraft isn't the only one skinny-dipping us on the avocado. Thank God there are plenty of lawyers out there who are selfless enough to protect us.

Sunday, December 17, 2006

What's Up with Triggerfish?

But, I can't recall ever having seen triggerfish on a restaurant menu before the fall of 2006.

Saturday, December 16, 2006

Affordable Cuts of Meat Part 2: Sirloin Tip Side Steak

And here's what I did with them:

Braised Sirloin Tip Steaks

Approx. 1 lb sirloin tip side steaks or other inexpensive "braising" steaks

1/2 white onion, finely diced

1 carrot, peeled & finely diced

1 stalk celery, finely diced

approx. 2 T minced parsely

1 tsp dried thyme

1/2 glass of red wine

1 cup chicken or beef stock

1. Heat a cast iron skillet over medium high heat, adding in a drizzle of olive oil when the pan is hot.

2. Season the steaks liberally with kosher salt and pepper and add to the pan.

3. After steaks are well browned on the first side, turn them over and add the carrot, onion, celery, parsley and thyme to the pan.

4. Cook until steaks are fully brown and vegetables are cooked translucent.

5. Add the red wine to the pan and let it reduce away, stirring up all the crispy bits at the bottom of the pan.

6. Pour in the chicken or beef stock and bring to a boil, then reduce the heat to around medium low and cover.

7. Allow to simmer, turning the steaks occassionally, for between 1 and 1-1/2 hours until the meat is tender.

8. Remove the steaks to a plate and cover with foil to keep warm.

9. Strain the vegetables and cooking liquid through a sieve into a bowl, pressing and mashing the vegetables to extract all the juices. Discard the vegetables.

10. Return the pan to the stove, turn heat to high, and add in the cooking liquid. Cook over high heat until reduced to a thick sauce.

11. Put the steaks on plates and drizzle with the reduced sauce.

I served my sirloin tip side steaks with some white rice and crusty bread and it was so good I forgot to take a photo of the finished product until I had almost finished the entire plate (and nothing looks more unappetizing than photos of half-eaten food!)

Braise, braise, braise, then reduce, reduce, reduce the cooking liquid. It can turn even the lowliest cuts of meat into an uptown meal.

Sunday, December 10, 2006

Unsolicited Advice for the Novice Cook (Part I)

1. Stop using margarine and start using butter. This has nothing to do with the health benefits of one over the other (and who can keep track of the latest scientific consensus, anyway). Butter has a creaminess and a texture and an enriching quality that you just can't get from margarine, which is essential salty vegetable oil, and it is indispensible for so many classic recipes. Unsalted butter is best--you can always add salt to a dish, but you can't take it away.

2. Use wine to deglaze pans. This is a simple step that adds so much. I keep a four-pack of those small bottles of white wine (the single-serving size) in my refrigerator for just this purpose.

3. Don't thicken sauces with flour or constarch: reduce them instead. Using a lot of flour to thicken sauces dates back to the days of Scientific Cookery in the late 19th Century, but it can be a crutch that ruins the texture of sauces. It's a snap to stir in a couple of tablespoons of flour to thicken something up; using cornstarch is even easier. But, they introduce an unpleasant gummy texture and, since they replace the long-simmering time required to make reduced sauces, result in a less-flavorful sauce. It's a shortcut that isn't worth it. Just turn up the heat and let the sauce bubble away until it is reduced down to the thickness you desire.

4. Make your own stock and use it liberally. Non-cooks seem to be overly impressed (or just puzzled) by people who make their own stock. I'm not sure why. It may take hours of cooking time, but the actual work involved is minimal--you just put a pot of water on to boil and toss in some meaty bones or chicken carcasses and some roughly chopped vegetables. Even if you roast your bones and vegetables first and skim the stock while it simmers, it's just not very labor intensive. And the payoff is huge. Using stock in dishes adds so much more flavor--and complexity of flavor--that once you start cooking with it, it's hard to imagine going back. It's an essential component of many classic sauces, and certainly a key for "high cuisine", but it also makes every day recipes--like chili and spagehetti sauce--richer and more flavorful as well. And, if you make a big pot you can freeze it in plastic containers and always have it on hand for cooking.

5. Control your own spices. The supermarket boasts dozens of pre-made spice mixes, like "chili seasoning" and "Italian Herbs", that are convenient but take all control of the flavoring away from you. Many contain non-spice additive like starch or MSG that, like using flour in sauces, is a shortcut way to get some thickness or body to cooking but, ultimately, result in an industrial aftertaste to food. It takes trial and error to learn what spices go well together and in what proportion, but over time you will achieve far, far better flavor than you would if you rely on a packaged mix to do it for you.

6. Get a good chef's knife and learn to chop and dice. I got a good chef's knife as a wedding present, and I'll never go back. There's no need to drop 75 bucks on a package that comes with 12 different knives (most of them serrated, which is the only way to make cheap metal able to cut) and a block to store them in. The same $75 will buy you a nice chef's knife, and that's really all you need--and I mean really. I have only two other knives (a thin boning knife and a bread knife), but in a pinch the chef's knife could substitute for either of them. Spend a little extra for a steel and keep the knife sharp.

Those chef-sized knives with a serrated edge are next to useless (q.v. bad kitchen equipment)--you can only use them for sawing, not chopping or slicing. With the cheapy knives (or a dull good knife), you'll never be able to chop or dice vegetables finely, which cuts out a whole spectrum of cooking. Once you have your good knife, it will be a prized tool for years to come.

These are just a few of my favorite kitchen lessons: I'll add some more down the road. I love hearing what other cooks have found to be their key tips and tricks, so please share!

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Lowcountry Nibbles - 7 December

Josh M, a student at MUSC, has started a new blog devoted to South Carolina barbecue. Just a few posts so far, but let's hope he keeps it going.

What does Brown's Barbeque in Kingstree, the Chestnut Grille in Orangeburg, and The Beacon in Spartanburg have in common? As the Post and Courier notes, they are all regular pit stops on the South Carolina political circuit. The Sunset Restaurant, a meat-and-three in West Columbia, is another noted hot spot (Republican, in this case) that didn't make the list.

A host of Charleston retaurants, including FIG, The Boulevard Diner, The Noisy Oyster, and Charleston's Cafe will be featured on the Food Network's "Hungry Detective" program Tuesday night (Dec 12th) at 10:30 PM.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Why do we tip?

Periodically since then--especially when I'm out at a restaurant and about to calculate the tip--I think about that thread, and it still disturbs me . . . primarily, I think, because of the apparent lack of thoughtfulness and the extreme self-righteousness that most people display when they discuss the issue of tipping. And, perhaps most disturbing of all, this entire discussion occured on an economics-focused blog, where you would expect the author and his regular readers to approach things in a rational, businesslike way and look at all of the incentives involved in the exchange.

And so I'm going to recycle a lot of my original argument here in an attempt to get to the bottom of this phenomenon once and for all. Why, ultimately, do we tip waiters in restaurants?

In almost every case people trying to answer this question look at the incentives from only a single angle: that of the restaurant patron. Why does the customer tip? What's in it for him or her? To insure prompt service, of course. This line of reasoning invariably leads to people puffing out their chests and huffing about the level of service they expect in a particular type of restaurant and how much it is worth for someone to bring them an iced tea as opposed to filling it themselves from an urn on the counter. And this gets annoying really fast, especially to anyone who realizes that the average diner has as little insight into all the other things going on in a waiter's or waitress's job than the average waiter has into what their customers have going on in their personal life outside the walls of the restaurant.

The incentive for a customer to tip is one factor, but it's not the really important one. In one sense, we still have the seemingly-archaic practice of tipping because it's good for the restaurant owner's bottom line. Why, after all, are grocery cashiers paid by the hour, teachers on a straight salary, lawyers on salary with huge bonuses, and salespeople on commission? Over time, these compensation schemes have proven to be the most effective way for a businessperson to get the desired behavior out of a particular type of employee. In the case of waiters, a tip-based compensation model helps insulate the owner from taking a bath on a slow night--if not enough customers come in the door, the wait staff takes home a smaller amount of money. Waiting tables is very much a customer-facing sales position, and any waiter who has figured out how to upsell tables with appetizers and drink specials understands that tipping is essentially a slightly-unstable commission system.

Tipping works out just fine for the restaurant owners. If it didn't, and moving from a tip-based scheme to a flat hourly or salaried package would actually ensure better performance from the staff and higher returns for the restaurant from all the pleased repeat customers, you can bet your sweet bippy you'd see more and more restaurants posting "Please, no tipping" signs and paying their waiters a regular wage (like most grocery stores now do for bagboys).

But, the real key lies in the incentives for waiters or waitresses to work for tips. The federal minimum wage laws provide for a "tip offset", which allows a restaurant to pay its employees a greatly-reduced minimum wage of $2.13 per hour, provided that when they add in tips a waiter or waitress's total hourly take exceeds the minimum wage. From a practical standpoint, since a waiter at even a mid-priced restaurant can take home 30 or 40 bucks for a 4-hour shift, this means that waiters are working primarily for the tips.

Ultimately, it's the waiter's total take-home--and the opportunity cost--that matters. If the total wages and tips combined did not exceed what that person could reasonably expect to make in another line of work, then that person would likely move on to other jobs. From the restaurant owner's point of view, if the diners all suddenly turned into my step-father-in-law and started tipping only 3% on their checks, then likely many of the restaurant's servers would quit, and the owner would have to raise the hourly pay to attract and keep enough workers to run the business, which means labor costs would go up, and in the end the owner would have to raise the food prices to compensate--which means the diners would wind up paying for the service in one way or another.

Essentially, the waiter labor market is at an equilibrium where, on average, the amount of money the restaurant patron is willing to pay (whether out of conformity or guilt or pride or sympathy or whatever) is sufficient to supplement the tiny hourly wage paid by restaurant owners and attract enough people to serve as waiters.

So why do we tip? A commenter named Justin from David Friedman's site noticed an interesting fact about the tip jar on the counter of the coffee shop where he worked: "people tip more when there is a good deal of money already in the jar, and they tend not to tip much when it's empty." And why is that? The tip jar is a signal of the proper social behavior: Am I supposed to tip these guys for bringing me coffee or not--oh, look, a bunch of other people have tipped them, so that must be the right thing to do. I feel the exact same way at Andolini's Pizza, which has an "Instant Karma" jar on the counter that always prompts me to leave a tip even though there's not really any waitress service, just because I'm worried the people who work there will think I'm a cheapskate if I don't.

We tip because everyone else does. Would it make a difference if we all decided overnight that it's a silly convention and we weren't going to follow it anymore? I've heard a lot of ludicrously convoluted rationalizations for how people arrive at a tip amount other than the standard 15% (like timing out how long it takes a bartender to fill and deliver a beer glass and backing into the tip from a reasonable hourly wage), but amid all the seemingly-relevant detail these explanations universally ignore the fact that the customer and the waiter aren't negotiating before the meal and agreeing on a mutually acceptable price. Chest-Swelling Consumer Boy may think all a waiter's effort in taking orders, delivering plates, and filling drinks is worth only 2 bucks per person per meal, but the waiter may have a different opinion, especially if he is going to serve only 20 customers in a four-hour shift.

The restaurant tipping system essentially runs like some of the quaint vegetable stands I've run across in New England, where the proprietor lays out the vegetables, puts an "honor system" jar on the counter, and leaves, allowing customers to deposit whatever amount they see fit. Whether one particular shopper puts in a nickel or a twenty-dollar bill for a pumpkin doesn't really matter; but, if in aggregrate all the vegetables disappear and there's practically no money left in the jar, you can bet the farmer isn't going to bother to keep the stand running for very long.

We tip because everyone else does, and because it works out okay for both the restaurant owner and the waiter. It's silly and nerve wracking and, when trying to calculate the tip on a dinner for six after one too many glasses of wine, prone to grievous errors. But it's not going anywhere any time soon.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

What's an Organic Fish?

It makes you wish they could just label things "good fish" or "not so good (but cheap) fish."

Lowcountry Nibbles -- 29 November

- Charleston's own Lee Brothers (Matt and Ted, that is) are getting tons of press these days, promoting their first cookbook. Here is a typical example. The Lees have established a successful writing career and, by all accounts, are pretty good cooks, too. But, their biggest talent seems to be clipping Yankees. Their "Lees Brothers Boiled Peanut Catalog" offers such bargains as two quart jars of Duke's Mayonnaise for $13.25, a box of 8 Moon Pies for $12.95, and a case of Royal Crown Cola for $22.95. Nice work, boys.

- Michael Fechter's Orphan Productions is staging a "Charleston Chef's Auction" via eBay, where donors can bid (starting at $1,000) for a private dinner for 8 prepared by one of an array of leading Charleston chefs. Details at http://www.experimentingratitude.com/sponsor.html

Sunday, November 26, 2006

It's the First Quarter, and the Home Team is Trailing

Why is it much more frustrating when something is close to being really good but falls just short than it is when something just plain stinks?

That was the feeling I took away from my first experience with Fiery Ron's Hometeam BBQ, which just opened up in West Ashley. I've been watching for months (or was it years?) while the old 1940s-era filling station on Highway 61 was gutted and completely renovated. It was always a cool-looking building, and I hoped it was going to be transformed into something interesting and exciting and not just another law office. A few months ago a sign appeared announcing, "Coming Soon: Home Team BBQ", and my heart soared. A barbecue joint was the perfect thing for that old gas station, and Charleston is still two or three good barbecue restaurants light for a town of its size.

Home Team BBQ has all the right ingredients for becoming a classic Charleston dining spot. Mind you, I don't mean a classic South Carolina-style barbecue joint, for that it is clearly not. The traditional Midlands and Lowcountry BBQ restaurant has all the atmosphere of a church family night supper, down to the folding tables and chairs and white cinderblock walls. They serve pork from a big buffet along with hash and rice and banana pudding, and they are frequently open only Thursday through Sunday. And they would never ever even think about serving beer.

Home Team is nothing like this, but to my mind it doesn't need to be. If you need the true local flavor, there's the Bessinger family and Momma Brown's and J. B.'s Smokestack and Sweatman's up in Holly Hill. Home Team is much more of a BBQ joint in the Memphis or Texas mold. They serve smoked pork, chicken, ribs, and, oddly enough, tacos. There's no hash anywhere to be seen.

The building is stylishly reworked, with shiny metal walls and funky barstools and nice, solid tables and chairs. There's a full bar and TV screens--a good sign that this could be one of those places where you go with the boys to catch the big game and knock back a platter of ribs and a few cold ones. To top it off, they're open until 2:00 AM and have booked a series of live blues and roots music performers to play, so it could turn into a pretty good nightspot, too, conjuring up echoes of the old Beale Street and McLemore Avenue joints in Memphis in the 1920s and '30s, which were more beer halls than restaurants and served ribs and pork sandwiches to the late night revellers living the birth of the blues.

So it looked promising. I took the whole family for lunch, and we ordered BBQ Pork Sandwiches for the two adults (one with Brunswick stew on the side, the other with baked beans) and a barbecue chicken taco for The Six-Year-Old. The meat was quite good: smoky and tender with some nice little crispy bits. I really liked the sauce, too, which is a spicy red tomato & vinegar concoction after the Texas style.

But somehow the whole thing didn't quite come off. The ingredients were all there, but the execution was wrong.

For example, take the sandwiches. We ordered ours on Texas Toast, which seemed more in keeping with the restaurant's style than a regular hamburger bun. The sandwiches arrived and, lo and behold, the bread wasn't toasted--in fact, it wasn't even warm. "This is NOT Texas Toast," The Wife said (and she can get pretty crabby when it comes to matters gastronomical). "Texas means big, which means thick slices. And toast means toasted. Heated until crispy and golden brown. Preferably with lots of butter. This is just thick bread."

The menu promised pickles on the sandwich, but we got none. Pickles would have added some nice crunch. And, the sides left a lot to be desired. For one thing, they weren't included in the $5.95 price of the sandwich but had to be ordered a la carte at $1.95 a pop. The Brunswick stew was pretty good, the baked beans rather bland. The "Mac n' cheese" was actually some sort of penne pasta in a thin, creamy white sauce. Guys, this is a barbecue joint, not a bistro. Macaroni and cheese means macaroni, not "pasta", with thick gooey yellow cheese, baked in a pan till it sets up. The Six-Year-Old is a macaroni and cheese gourmand, a fan of everything from the blue box Krapft variety all the way to homemade fetuccini tossed with butter and Parmigiano Reggiano, but he turned up his nose after one bite. And, for the record, if a side dish costs $1.95 (as all of the Home Team ones do), it really needs to come in larger portions than a half-filled 4-oz styrofoam cup.

On the other hand, The Six-Year-Old raved about the chicken taco, declaring it the best in town and declaring he wanted to come back again and again. So, there is hope for the Home Team. Any place where a dad can have a beer and eat some ribs and keep his kid happy at the same time has a bright future.

So, come on, team. I'm rooting for you. Bowl season is coming up. I want to knock back a sloppy red-sauce-soaked sandwich on grilled Texas Toast and wash it down with a couple of cold ones while watching the game. Toast the toast. Or, better yet, install a big griddle and toast the sandwiches with the meat and sauce already on them. And serve it up in wax-paper-lined basket with a big mound of the selected side item.

And don't forget the pickles. It's the little touches that count.

Thanks to The Wife for the title for this post. When it comes to snarky parting shots, she's the queen.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Ping Island Strike Blog

Saturday, November 18, 2006

Regrettable Food Department

Jalapeno mayonaisse adds kick to Texas Tuna Burger

Is this from the food section or the crime report?

Lowcountry Nibbles

Robert Barber, having narrowly lost the Lt. Governor's race to Andre Bauer, has announced he will now focus his energies on rebuilding his Bowen's Island restaurant, which burned to the ground last month.

Fiery Ron's Hometeam BBQ at 1205 Ashley River Road (Highway 61) is slated to begin serving food on November 20th. Not sure what the barbecue will be like, but the bar is already open and is hosting blues and bluegrass shows. Co-owner Aaron Siegel used to be the executive chef at Blossom.

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Squid Ceviche

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Guava

Most of the grocery stores in my area have the requisite stock of apples (the same 6 varieties), oranges, pears, and bananas. Maybe the occassional coconut or whole pineapple if you want to get crazy. But, the Publix (on Sam Rittenberg Drive) can always be counted on to have at least a dozen exotic fruits that I've never purchased before. The other day I stumbled across a bin of guava whose smell was so strong and sweet and tempting that I had to buy a few.

I sliced a few and ate them, but what better than a guava mojito? (It was really good, but since I had to peel, puree, and strain the fruit myself, I'll probably save the trouble in the future and just buy guava nectar.)

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Lunch on Daniel Island

It's also built on an old swamp and is mosquito infested.

I lived on Daniel Island (in an apartment) when I first moved to Charleston. And, for the better part of the last five years, I've worked there. My overall conclusion is that, based upon this brave New Urban experiment, the planners and theorists need to go back to the drawing board and figure out how any place created with "humane urban design" could end up without any good places to eat lunch.

This doesn't mean there aren't any restaurants on Daniel Island. And it doesn't mean that there aren't any fancy places to buy lunch. There are, in my view, far too many of these. I would just prefer a little less "fancy" and a little more "good".

I won't name any names, because it's not the fault of any one particular restaurant. Maybe the rents are too high to support my type of lunch joint. Or maybe the Island's residents and employees are too classy to patronize such places. Rather than pick on one, let's roll them all together into one composite business--call it McSnoot's Cafe & Bistro--and address them as a genre.

When you enter McSnoot's, you notice it's a nice room. A good heavy door, lots of windows, tasteful art on the wall. There's no linoleum on the floor or vinyl-covered booths--all hardwoods and tile and solid wood furniture. And there's no long queue of patrons waiting to order at the counter. You pick your seat--whichever one you'd like, usually, since McSnoot's is rarely at full capacity, even during peak lunch hours.

The menu is nicely printed on thick, decorative paper, and has only a small number of options--soups and sandwiches mostly. But, don't worry. These aren't run-of-the-mill ham and turkey sandwiches. That wouldn't be "Island Living." You can expect your reuben to come on ciabatta instead of plain old rye, and with a blue-cheese coleslaw subsituted for the sauerkraut. And nothing dresses up a turkey sandwich like some alfalfa sprouts and brie cheese.

One note: please don't ask your waiter for a Coke. McSnoot's doesn't carry soft drinks, but they do have a fine selection of spiced teas and freshly-squeezed juices (for $2.25 a glass--quite reasonable for a lunch beverage.) Sip that spiced tea slowly, for you'll probably only see your waiter about once every fifteen minutes. There are six other tables in the cafe, after all. But, all in all, they'll get you in and out in no more than an hour-and-fifteen minutes--not bad for your typical lunch break. Lunch for two, with a tip for the rather bored waitperson, will run you

about 26 bucks. It's hard to beat island living.

These lunch spots were dumpy, with old posters on the wall and lots of greasy smoke in the air. And they were crowded, too, turning as many patrons in 15 minutes as a Daniel Island eatery is likely to serve all day. And you'd be rubbing elbows and bumping knees with a wide range of people--bankers in suits, nurses in scrubs, utility workers in muddle coveralls, and batty old ladies out shopping for wigs. And we would walk away all told for about $10 bucks for the two of us. And, boy, was the food delicious.

Friday, October 27, 2006

Remembering Bowen's Island

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Synergy

This technique not only makes the preparation easier but cuts down the clean up, too: a true one dish meal. And, since I usually cover the leftover bird with plastic wrap and put the whole pan in the refrigerator, I usually don't even have to wash the pan that night.

Best of all, potatoes roasted in chicken fat are fabulous--rich and tender and spiced just right. So good, in fact, that it has made me want to start exploring cooking with schmaltz--if it makes potatoes so wonderful, imagine what it might do for other foods?

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Great Tacos at El Mercadito

I had read about El Mercadito a number of times in the past, and all of the reviews began with something along the lines of "who would expect to find great Mexican food way out on John's Island in a Piggly Wiggly shopping center?" So, it has been on my list of Charleston restaurants to try for quite some time. This weekend I finally made it out there for lunch.

When I first opened the menu I was pretty disappointed. I was expecting some fantastic roll call of Mexican specialties that you just can't get on the Carolina coast--things like mole and real tamales and meatballs in chipotle sauce. What I found looked like the same menu you see in every one of those La Hacienda/Monterrey/San Jose/etc. restaurants that have Mexican (or, at least, Latino) owner/operators but apparently all share the same distributor and recipes--including, of course, the "Speedy Gonzales" #1 Lunch Special , which must appear on about eighty-three thousand Mexican restaurant menus in the Southeast.

And then I spied, amid all the standard franchise tex-mex numbered combos, a picture of a platter of tacos, and I knew immediately what I was ordering.

I was about to write, "El Mercadito has real tacos," but I really can't say that for sure, having never been to Mexico and not knowing for sure even if Mexico is the home of the real taco. If you believe food writers (like Mark Bittman, who recently published a nice column on "real tacos" in the New York Times) then these are the real thing. And, real or not, I can say with certainty that they are GREAT tacos.

First, each taco is served on two soft, warm corn tortillas (not a deep fried corn tortilla shell nor a chewy flour "soft taco" tortilla). And, second, you get a choice of five great meats: al pastor, pork carnitas, carne asada (beef), something I can't remember (probably chicken), and cabeza. I knew the last one literally means "head", but the menu had it translated as "beef cheeks". I ordered three tacos, including one with cabeza, figuring that something so odd-sounding had to be good. And, as luck would have it, they were all out of cabeza (or, at least they claimed to be out of it. As with the seared pig trotters at Amuse, I'm starting to suspect that whenever I order something unusual the waiter takes a look at me, figures I don't look like an adventurous enough guy, and tells me they're out of it just to spare me from being disappointed.) So, I ended up with a carnitas, a beef, and an al pastor.

The latter was probably my favorite--a hard call to make, admittedly: all the meats were tender with crisp edges and smoky and fantastic and miles away from the typical overly-spiced steamed ground beef. Tacos al pastor are made from a big hunk of pork coated with spices and cooked on a rotisserie, then shaved off as the tacos are ordered--much like the giant blocks of lamb meat from which gyros are carved.

El Mercadito dresses its tacos not with a big wad of shredded iceberg lettuce and gobs of pasty colby-jack but rather with onions and a little cilantro and nothing else. Wedges of lime are placed on the side, and a small rack of three salsas--pico de gallo, salsa verde, and a rich red chile sauce--are served alongside. And the tacos were fantastic.

Surfing the web as I worked on this post, I noticed a review that suggested El Mercadito recently underwent a renovation to make it into more of the classic "American Mexican" restaurant that Southern diners have come to expect--explaining the presence of the infamous "Speedy Gonzales" lunch combo.

I say more power to them. If the bland, standard menu and baskets of chips and salsa get more patrons in the door and helps pay the bills and keeps the restaurant open that's fine with me. As long as they keep tacos al pastor and other genuine delicacies tucked away somewhere in the back of the menu, I'll be happy. And, I'll be coming back for more.

Friday, October 13, 2006

Low Prices Don't Rule in the UK

Whereas in the U.S. (as the huge success of the Super Walmart grocery business has proven) low-cost trumps all, in the UK less than 50% of shoppers say they consider price when selecting food. British food habits are changing: celebrity chefs are hot on UK TV, Britons are both eating out more often and cooking more fresh meals from scratch at home. Quality--or, at least, the perception of quality--sells now, with premium and organic brands growing in market share.

It's an interesting sign that while low prices are an important factor in retail success, they aren't everything. It will be interesting to see if similar trends begin to play out here in the U.S., where the market seems to be increasingly polarized between high-end/organic/expensive (WholeFoods) and low-cost/low-quality/industrial (Super WalMart), without much room in between for people whole like traditional, fresh, wholesome foods.

Monday, October 09, 2006

Trumer Pils

There's a new beer on the Charleston scene . . . or, at least, that was going to be the lead line for this post, until I surfed the web a little and realized I may be a bit behind the times. So, to be more accurate . . .

There's a beer that's new to me on the Charleston scene: Trumer Pils. The label bears two locations: Salzburg and Berkeley, which indicates the beer's origin. The recipe is that of the Trumer Brauerei, a small Austrian family brewery. It was brought to the U.S. two years ago by Gambrinus, Co. of San Antonio, which imports Corona, Modela Especial, and other Mexican beers and owns the breweries that make Shiner Bock and Pete's Wicked Ale. The U.S. version of Trumer Pils is made in the former Golden Pacific Brewing Company plat in Berkeley, California. It is currently distributed in only a limited (but growing) number of states. Charleston, in fact, was the first market in which the beer was released.

Okay, okay . . . but how does it taste? Pretty good, in my view. It's a very light, clean tasting beer, with a nice bitter bite at the end. It's definitely a beer you would want to serve ice cold.

So, even though I'm a year or so late noticing it, it's a beer that is fairly unique to Charleston, and one I'm sure I'll pick up again in the near future.

Sunday, October 08, 2006

The Wild Ride Continues

Flat-Iron Steak

I've always been a fan of low-budget cuts of meats. Big ribeyes or tenderloin filets are great treats every now and again, but they are pricey and best suited (for my pocketbook, at least) for special occasions. Many of my favorite dishes are rooted in creative ways to transform the less expensive cuts of meat into tasty delicacies (Braised short ribs, brisket, coq au vin, and osso buco come immediately to mind). While many of these require hours of long, slow cooking and are therefore not ideal for weekday cooking after a busy work day, I'm always on the look out of new, tasty, affordable cuts of meat.

So enter the flat-iron steak. I first saw this version of steak cropping up at my local Publix supermarket. It looked like a pretty nice cut and, at around four bucks a pound, was very reasonable priced. So I bought one and took it home and made a very passable steak dinner from it. It's now entered my list of regular weeknight dishes which can be made quickly and, at less than 2 dollars a serving, isn't going to break the bank.

But what is a flat-iron steak? As it turns out, it's a rather recent cut, and one with a lot of science behind it. Also called a top blade steak, the flat-iron is a cut taken from the top of the chuck (don't forget your handy cuts of beef chart, available here) and apparently is the result of some intensive research from a team at the University of Nebraska's Institute for Agriculture and Natural Resources. Working in collaboration with a team from the University of Florida in a project funded by the National Cattlemen's Beef Assocation (yes, there were many people involved in this work), the Nebraskans systematically studied and characterized over 5,500 muscles in the beef chuck and round, searching for new, tender, and inexpensive cuts that traditional butchers had missed (full story here).

One of the cuts they identified was the flat-iron. Because the top shoulder has a big mass of connective tissue running down the middle of it, it looks tough. But, if you cut against the grain and remove the connective tissue, you are left with two thin filets that are exceptionally tender.

I'm always a little suspicious of food born from the science lab, but the flat-iron doesn't involve chemical concoctions or anything like that. It's just a different way to cut up the chuck. Some butchers claim that the flatiron is second only to the tenderloin in overall tenderness. I'm not sure how to verify that, but I cook my flat-iron steaks in the same way I do tenderloin filets, and they always come out great. Below is my standard stove-top version:

Pan-Seared Flat-Iron Steak with Red Wine & Shallot Reduction

2 flat-iron steaks (about 4 to 6 oz each)

coarse kosher salt & pepper

1 shallot, peeled & chopped

2 T parsley, chopped

1/2 cup red wine

1T olive oil

1T butter

Heat a frying pan over medium high heat. When it's hot, add the olive oil. Season the steaks well with salt and pepper and add to pan. Cook on both sides till outsides are brown and crispy--about 3 minutes per side for rare, longer for more doneness.

When steaks are done, remove to a plate and cover with foil to keep warm. Return pan to heat and add butter. Once it is melted, add the parsley and shallots (the smell of the shallots hitting the pan is one of my favorites) and cook until translucent. Turn heat to high, add red wine, and deglaze the pan, stirring with a wooden spoon to get up all the brown bits. Let the red wine reduce till it's a thick sauce; I usually uncover the steaks a pour any of the remaining meat juices into the frying pan, too.

Put the steak on a plate, pour the reduce sauce over the top, and serve.

I usually serve this with mashed potatoes and either green beans or a salad. From start to finish I can do that meal in less than 45 minutes, with the steak taking only 15 or so, so it's perfect for a weeknight.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

No Mo' Mofongo

I was back in Puerto Rico this week for another quick (one-night) trip, but this time I got to stay long enough to try more than the mojitos at the hotel bar. I got in in the late afternoon, early enough to enjoy the breeze and a couple of cold Medallas (a local Puerto Rican beer) at the hotel's ocean-side bar and watch out over the waves as the sun set.

Dinner that night was at the Ceviche House, a Peruvian restaurant (I know, I know, as with the mojitos I'm having a hard time keeping my regional specialities straight--but, it's not like I can get Peruvian food in Charleston, South Carolina . . .), and I was fortunate to be eating with a bilingual colleague who could help me not only navigate the menu but also chat with the waiter about the food and its preparation. The dinner was good--I had a nice dish of steak in a peppery sauce--but the appetizers stole the show.

We had, of course, ceviche, which was fantastic--firm, tasty fish marinated in a tangy blend of citrus, onions, and peppers. But, my favorite was the fried yuca. Yuca is a potato-like tuber, better known in the U.S. as cassava. It was cut into wedges and deep fried, and they served it with two different sauces. The first was a white, creamy sauce with just a hint of spice; the second was a much more pungent green sauce that was very strong with garlic. Both went quite well with the yuca wedges, but the spicier green sauce was my favorite. In Peru, the waiter told us, they would serve just one sauce with the yuca, which would be sort of a combination of the white and green sauces, but in Puerto Rico--where the food isn't as spicy as in other parts of the Caribbean--they had to serve the milder, creamy white sauce or none of the locals would eat the dish. The yuca has a very distinctive taste to it--definitely somewhat like a potato, but firmer and with a subtle aftertaste. We made short work of it.

But, yes, I finally did get a chance to sample the local Puerto Rican cuisine. At lunch the next day we went to Mi Casita, an unassuming place in a strip mall, but my colleague assured me it was great local food. As soon as I saw Mofongo on the menu, I knew what I was going to have.

Mofongo is a Puerto Rico staple--a hearty starch that is the base for many different types of meals. It is made from green plantains which are fried and then mashed with garlic and pork cracklings. In some places the Mofongo is rolled into balls, and often it is filled with meat or seafood. At Mi Casita they mold it into a large tower-like mound and cover it with your topping of choice, which include shrimp, beef in a creole sauce (pictured above), and carne frita (fried pork). We ordered the beef and the carne frita, which I judged my favorite. The pork bits were salty and juicy--fried lightly without a batter--and went well with onions and peppers that came alongside it.

As for the mofongo itself, it was fairly bland (especially considering it was mashed with garlic), but had a great heavy texture. You might think that the plantains (being related to bananas) would be sweet, but they really are not--especially the green ones. By itself I wouldn't think mofongo would be much of a dish, but it goes perfectly with highly-flavored accompanyments like the pork or the beef. And, the menus really ought to carry a big red label saying, "WARNING! THIS MEAL WILL STUFF YOU SILLY!"

I had wolfed down only about a quarter of my carne frita before I started to feel full, but I soldiered on. Five minutes later I had put away a good about half of the mound of plantain mush, but then I had to throw in the towel. I was painfully full. The waiter laughed and said something to my Spanish-speaking colleague when he cleared away our plates, and I picked up just enough to figure out what he was saying. "He was making fun of us, wasn't he?" "Yes," she said. "But I won't tell you what he called you."

It stung my pride a little, but there wasn't much I could do. We had an afternoon flight, so we left Mi Casita and drove to the airport. I must have checked in and went through security and all that, but it's all just a plantain-induced haze in my memory. I was stuffed. I was sleepy. It was all I could do to trod down to the gate and get on the plane.

I managed to stay awake long enough to watch the island fall away beneath us as the plane arced out over the Atlantic and back over the city then headed northwest toward Atlanta. Then I fell into a cozy, satisfied, mofongo-fueled sleep.

Monday, September 25, 2006

Crab Cakes

We spent last weekend at Sunset Beach, North Carolina, with my parents, just hanging out and relaxing and--of course--eating. Blue crab was the order of the day. From the dock (pictured above), my father and my son teamed up with a single crab trap baited with chicken necks and caught so many crabs in the first 24 hours--almost two dozen--that they stopped throwing the trap in the water: we'd caught all we could eat.

We spent last weekend at Sunset Beach, North Carolina, with my parents, just hanging out and relaxing and--of course--eating. Blue crab was the order of the day. From the dock (pictured above), my father and my son teamed up with a single crab trap baited with chicken necks and caught so many crabs in the first 24 hours--almost two dozen--that they stopped throwing the trap in the water: we'd caught all we could eat.Or, perhaps more accurately, we'd caught all that anyone cared to clean. It isn't a fast process. My mother and I picked the crabs, using nutcrackers and little skewers and any other small tools we could find to eake out the tender white meat from the shells (we didn't have any crab pickers--little hook-like devices that make the cleaning much, much easier). Saturday night for dinner I made crab crakes. My recipe, which is one of those things that is very imprecisely measured and whose ingredients vary each time based upon what I have on hand, went something like this:

Crab Cakes

One big plastic tub (approximately 1 lb.) of blue crab meat, boiled or steamed, removed from shell, and well picked-over

1 egg

1 Tbsp dijon mustard

2-3 Tbsp mayonnaise

1/2 small onion, minced

1/3 medium green pepper, minced

several pinches of minced parsley

a few dashes of hot sauce

salt & pepper to taste

Approx. 1/2 cup bread or cracker crumbs, plus more for coating

butter and/or olive oil for frying

1. Combine the crab, egg, mustard, mayo, onion, green pepper, hot sauce, salt, and pepper in a large bowl and mix well.

2. Stir in enough bread or cracker crumbs to bind the mix together.

3. Spread the remaining bread or cracker crumbs on a plate near the stove.

4. Heat a large frying pan over medium-high heat, adding in enough butter and/or olive oil (I use a mixture of the two) to coat the bottom of the pan in a thick layer.

5. While the oil is heating, pat the crabmeat mixture into small, thin cakes (about 3 inches in diameter and 1/2 to 1 inch thick) and dredge on both sides in the remaining bread or cracker crumbs.

6. Saute the cakes in the butter or oil, turning once, until golden brown. This usually takes 3 to 5 minutes per side.

7. Remove to a plate lined with paper towels and allow to drain.

8. Serve with cocktail sauce or the sauce of your choice.

Monday, September 11, 2006

Jim's Steaks

I was in Philadelphia on Thursday, and that meant cheesesteaks for lunch. Our host, the inimitable Rob Armstrong, is a Philly native, and he offered to serve as our guide, driving us through a maze of narrow one-way streets down to South Street. Jim's Steaks is at the corner of South and 4th.

It's a great old art deco building, a small, two-story place with a floor of tiny white and black tiles and larger white tiles on the wall. The downstairs is narrow. To your right as you walk in the door is a single row of stools along a narrow counter for dine-in customers (there's more dining space upstairs); to your left is the line where you order. And the whole place is filled with the fantastic aroma of sizzling beef.

The most impressive thing about Jim's is the grill--griddle might be a better term, since it's a single long metal surface. As you stand in line preparing to order, you're right in front of it and can watch the griddleman working the steaks. The meat is piled up along the griddle from left to right (from the customer's perspective), starting with a huge mound of paper-thin sliced top round. Using a giant flat spatula, the grillman works the meat from the left side of the griddle to the middle, flipping, turning, and chopping it with the spatula, moving it gradually as it cooks over to the right side of the griddle, where the fully-done meat nestles next to a massive pile of sauteeed onions. And, at the far left, is the classic emblem of the cheesesteak joint: a gallon-sized metal can of Cheez Whiz, its top removed, set right on the griddle to keep warm, a big ladle sticking from the top, ready for scooping. (Unfortunately, I didn't have my camera with me, but the images at the Roadfood site capture this experience well.)

Armstrong helped guide me through the proper lingo for ordering. You have a choice of Cheez Whiz (which should be ordered just as "whiz"), American, or Provolone cheese, and can add onions, peppers, mushrooms, lettuce, and tomato. Onions are special and are ordered via shorthand. If you want them, you don't say "with onions"; you just say "with". So, a Provolone cheesesteak with onions and mushrooms is a "Provolone with and mushrooms"; a Cheeze Whiz with no onions is a "Wiz without".

Much has been made about the ordering rules at Philly cheesesteak restaurants, with writers offering dire warnings that you'll be thrown out on your ear if you breach the protocol. In realilty, you just have to remember that Philadelphians are usually in a hurry and are not overly constrained by good manners. As long as you order quickly and don't hold up the line you'll probably be fine. But, saying "gimme an American with and peppers" is just fun.

Sure, CheezWhiz is available at every cheesesteak place, but I suspect that's some kind of cruel joke Philadelphians like to play on tourists. Armstrong got his with American cheese, and I followed suit. (American, in this case, is a thinly sliced white American cheese--much, much, much better than that yellowish Kraft cheese food stuff.) And it was GOOD.

"The thing that makes a great cheesesteak," Rob Armstrong said as we tore into our steaks at the little dining counter along the wall, "is not the meat or the cheese or any of that. It's the bread." And, I have to agree with him on that. Jim's uses 7" Italian sandwich rolls from Amoroso Bakery--itself a Philadelphia tradition--that are delivered fresh daily. And the bread is definitely different than the kind of soft hoagie rolls you get in the supermarket. The outside is slightly crusty, and the inside nice and chewy. It makes a perfect platform for soaking up all the juices from the steak and the melted cheese without getting mushy.

I washed my cheesesteak down with a Dr. Brown's Black Cherry Soda and was a happy guy.

Philadelphians argue over which joint has the best steaks. Pat's and Geno's--located on opposite corners of 9th Street and Passyunk Ave. in South Philly--often win high marks, but they also get tagged as "tourist spots." Jim's is right up there, too. Rob Armstrong confided that as good as he think's Jim's is, he actually prefers Geno's which "doesn't go through me as fast, if you know what I mean." (Like I said, he's inimitable.) But, I had no issues with it. Uncorrupted by any exposure to a Pat's or Geno's steak, I'm voting for Jim's.

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Muscadines are Here

Down at the Marion Square Market yesterday, I found tray after tray of muscadines for sale. This grape variety--often called scuppernongs, after one of the more popular varieties--is native to the Southern U.S. They start to ripen around the end of August and will be available until October.

The color of muscadines range from a bronzy green to deep purple. They are something of an acquired taste, it seems, and I can see why. The skins are very firm and have a bitter taste to them, but the inner flesh is very soft and sweet. When you pop one into you mouth, you have get crispiness and softness, bitterness and sweetness, all in the same bite. Eating muscadines always takes me back to my young childhood in Great Falls, SC, where some of my father's friends grew them out on their farmland and we would eat them fresh from the vines. They're a true Southern treat and won't be available for long.

Saturday, September 02, 2006

Welcome to France

Back to Nature

The lunch was pizza from Papa John's supplemented with bags and bags of Doritos and other snack chips, 2 liter bottles of soda (including lots of Mountain Dew), and bags of Oreo and Chips Ahoy cookies. (Yes, I do work at a software company--how did you guess?)

Now, I'm not one to put up my nose in the air and sneer at pizza, Oreos, and Coca-Cola. But, I've been on the road a bunch of the past month and, frankly, my diet has been nothing short of lousy--fast food grabbed in airports, candy bars from vending machines, take-out pizza and Chinese on the days when I've been at home but too tired to cook.

The tropical storm luncheon put me over the edge. I can't eat like this anymore.

This isn't one of those things where you think: gee I better cut back a little. This isn't an intellectual thing, nor a moral thing, nor a health thing. It's a raw physical revulsion to industrial food.

I'm shot. I'm through. I can't take another dose of high fructose corn syrup, guar gum, or modified corn starch. I want to purge my system, eat clean. And I don't mean wheat germ or bee pollen or any of that natural food store stuff. I mean just good old fashioned food from nature. I don't want to put anything into my body that wasn't available to humans before the Industrial Revolution.

It's also not an easy thing to do. At work, I'm surrounded by people who are too kind: they bring in Chick-Fil-A biscuits and Krispy Kreme donuts and bags of gummy worms and cookies and candies and pass them around for all to share. What a wonderful gesture! But, my stomach physically aches any time I think about another mouthful of candy or a bite of pepperoni pizza.

So, my plan is to go fresh & natural: no more fast food, no more candy and sodas. Coffee is fine, as is iced tea: foods made from packages whose ingredients list has no commas: "ground orange pekoe tea leaves." No more peanut butter crackers or donuts for breakfast. Fruit, lots of fruit. Good bread with real butter. Homemade meals. And, for Pete's sake, no more high fructose corn syrup.

I've done okay the past two days, but the challenge will be when I get back to work on Tuesday. We'll see how long I can hold out.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Twenty Four Hours, Four Flights, and One Mojito

I flew out for Puerto Rico at 4:00 PM on Sunday, changed planes in Atlanta, and got into San Juan just a little before ten. The tail end of tropical storm Ernesto was just passing by the island, and the tropical night was warm and rainy.

We were staying at the Ritz-Carlton, a massive ocean-front palace with a full casino and a spa lots of dark wood and marble in the lobby. So far so good. The problem was: I had an meeting the next morning at 7:30 am and, because of other commitments back home, a flight out at 2:30 PM that afternoon. All in all, just 17 hours on the ground, including sleep time. No time for sopa de arroz con pollo, no time for plantain tostones, and not even enough time for lechon asado (barbecued pig). Not even enough time to snap any pictures (I borrowed the one here from the Ritz Carlton website.)

At least I got a good mojito.

Okay, so it's really a Cuban drink, but the rum was Puerto Rican, and it was advertised as the specialty of the house at the Ritz-Carlton Lobby Lounge, where my colleagues and I had a drink and watched as the tropical rain pounded down outside. It seemed like the thing to try. And it was really, really good.

Mojitos are a big trendy drink in the U.S. now--so trendy that Delta airlines was flogging them onboard the plane on the trip down, made I'm sure from some high-fructose mix. Most mojitos I've had have been, frankly, pretty disappointing--a mess of soda water and undissolved sugar and annoying clumps of mint leaves. I've made them at home, too, but they've always come off as too strong--either too much of an alcohol bite from the rum or too sour from the lime.

So, when I took a sip of the one at the Ritz-Carlton and found it a perfect smooth blend of sweetness, sourness, and mint, I kept one eye on the bartender and took notice the few next times he made mojitos.

The ingredients were simple: rum, fresh lime juice, sugar, and mint with just a touch of soda (not half a glass of soda, as I've seen it made in too many places). And, smooth as it was, it wasn't because he skimped on the rum--the doses, in fact, were pretty darn generous. The key, it seems, was in the muddling. In most mojitos I've had, the mint is beat up a little in a cocktail shaker, sometimes with a spoon and sometimes with an actual wooden muddle. At the San Juan Ritz, the bartender used an actual mortar and pestle (both wooden, I think) to not just crush the mint leaves but to pulverize them. The resulting drink was not clear with little bits of green mint leaves floating around inside but rather a bright, neon-green liquid. Lots of little bits of mint were suspended in the liquid, but so tiny that they didn't stick to your tongue and clog up the works while you were drinking. It was so good that I wanted a second one, but I had to be up in five hours, so it was off to bed.

The only other island specialty I got to sample was the coffee, which is grown locally and brewed up thick and strong--more like an espresso than the typical weak mainland brew, and served in appropriately small cups. At our meeting that morning, most of the attendees took their coffee con leche, with a health dose of warm milk added and mixed in. A carafe full of milk was kept warming on one of the coffee-machine burners just for that purpose. I had mine black, and its strong, rich flavor helped kicked the morning into gear. Then it was a blur of meetings, high speed rides to the airport, and racing for the airplane gate.

With any luck, I'll be heading back to Puero Rico again in the near future, and next time I plan on staying at least long enough to eat dinner.

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Food Origin Myths

I’ve long been fascinated by food origin myths—particularly the stories of how today’s popular foods came to be. The more you read these types of stories (such as who invented the ice cream sundae), the more you notice some common themes, such as these:

The sole inventor. One common element of food origin stories is that the item in question was fabricated by a single person. Food origin myths speak to the fundamental human need for certainty. It just isn’t satisfying to think that a lot of people were making ground beef patties in the mid-to-late 19th Century, that many of them started serving the patties on various types of bread, including soft white buns (which were becoming more popular after the Civil War), and there were many names for such sandwiches but one of them—hamburger—over the course of decades won out and became an iconic food. It’s much more dramatic to think of a single moment when a single person executed the deed. We prefer the certainty and good stories to the messy, ambiguous facts of history.

The Eureka! Moment and the Last Minute Improvisation. Just as there’s something compelling about the concept of a sole inventor, if the circumstances under which he or she conceives the invention are dramatic, then the story is just that much better. Sir Isaac Newton’s being hit on the head by an apple and coming up with the concept of gravity all at a flash makes for a much better story than his puzzling a theory out over the course of years, informed by lots of reading and discussions with friends and colleagues. The same is true in food origin myths. It’s rare to hear a story about how a café owner experimented for years with new sandwich combinations, introducing a long line of duds (smoked salmon, olives, and green beans on toast, anyone?) before finally finding a combination of corned beef and sauerkraut on rye that people seemed to like and ordered again and again.

The Hamburger

The hamburger provides a great example of food origin myths at work, and--in classic food myth fashion--there are many competing stories. Most of them demonstrate the elements of the sole inventor and the last-minute improvisation. These stories can be found in a range of sources, but Linda Stradley's "History of Hamburgers" at What's Cooking America provides a good compilation. A few representative examples:

- Hamburger Charlie: 15-year-old Charlie Nagreen from Seymore, WI, was having little luck selling meatballs from a cart at the 1885 Outagamie County Fair. Deciding that business was slow because it was too hard to eat meatballs while walking around the fair, he had the brainstorm to flatten out the meat and server it between two slices of bread. His creation was an instant hit, and Nagreen returned to the fair to sell them every year until his death in 1951, earning the nickname "Hamburger Charlie".

- The Menches Brothers: Frank and Charles Menches, traveling fair concessionaires from Akron, Ohio, were working the fair at Hamburg, NY, in 1885 when they ran out of pork for their sausage-patty sandwiches. The local butcher had stopped slaughtering pigs because it was too hot, but he offered the brothers ground beef instead, which they substituted in their sandwiches, naming their creation "Hamburgers" after the town.

- Louis Lassen: Louis Lassen, proprietor of a lunch wagon in New Haven, CT, specialized in selling steak sandwiches to local factory workers. One day a customer in a hurry asked for something quick that he could eat on the run, so Louis ground up some scraps of steak and served them between two slices of bread.

In many versions of the Louis Lassen story the explanation is more mundane: Louis was an economical guy and came up with the hamburger as a way to use up leftover steak scraps. This latter story makes much more sense than a last-minute idea for a hurried customer (after all, would a sandwich made from ground meat scraps be any quicker or more portable than a regular steak sandwich?). But, the improvisational details add drama to the story and make it all the more compelling.

And that's why we love these stories so much.

Sunday, August 06, 2006

A Compelling Wild Ride

Sweet Tea the Simple Way

I'm never sure whether it's worth passing on little tips like this, because once you start using them they seems so obvious. But, for years I was completely unaware of simple syrup, so I can only figure other people must still be, too.

I've lived in the South all my life, and for all my life I've heard complaints about how once iced tea has been cooled it's impossible to sweeten it. These complaints usually come when I'm traveling in the North with fellow Southerners or here at home when eating at one of those snooty upscale places that have the nerve to say, "we only have unsweet tea." And I'll watch as a dedicated sweet-tea lover dumps packet after packet of sugar into the glass, only to have it sink undissolved to the bottom, leaving a glass of unsweet tea with an inch of sugar sludge at the bottom.

I gave up on trying to sweeten tea with granulated sugar many years ago and just drink it unsweetened--which is fine with me, since I like both sweet and unsweet tea. But, my openmindedness seems to be uncommon: most people are either dogmatically sweet or unsweet in their preferences and abhor the other kind. This was always a problem when people would drop by my house unexpectedly: I like to offer them something to drink, and most people like iced tea when they're not up for something alcoholic, but my visitors always seem equally split between the sweet and unsweet camps.

But not long ago, while trying out recipes for various summertime drinks like the mojito, I stumbled across a trick that is perfect for sweetening even the iciest-cold iced tea: simple syrup.

Simple syrup is just plain old sugar dissolved in a small amount of water. But, for sweetening drinks, it's magic: unlike regular sugar, the syrup blends right in and merges with the cold liquid. You can use it for all sort of alcoholic drinks, too, like margaritas and daiquiris, and stop messing around with those sickly-sweet mixes.

So, now I always have pitcher of unsweet iced tea in my fridge along with a little container of simple syrup. Pour a splash of syrup in the bottom of a glass, add ice and unsweet tea, and even the most die-hard sweet tea fan will be satisfied.

Now if we could just get those snooty restaurants to start putting little pitchers of simple syrup on the table . . .

Simple Syrup

Use a 1-to-1 ratio of sugar to water. So, to make 2 cups, bring 1 cup of water to a boil and stir in 1 cup of sugar, stirring till the sugar is fully disolved. Cool and store in a closed container in the refrigerator.

Monday, July 24, 2006

BAD Food (Airline Edition)

In BAD: or, the Dumbing of America, Paul Fussell draws a distinction between bad things and BAD things:

Bad is something like dog-do on the sidewalk, or a failing grade, or a case of scarlet fever--something no one ever said was good. BAD is different. It is something phony, clumsy, witless, untalented, vacant or boring that many Americans can be persuaded is genuine, graceful, bright, or fascinating. . . . Bathroom faucet handles that cut your fingers are bad. If goldplated, they are BAD.

And, he procedes for some 200 riotous pages to enumerate the many BAD things that can be found in today's culture, from BAD advertising to BAD television.

I was reminded of his book last week on a flight from Atlanta to San Francisco, during which I was handed ("tossed" might be a better word) my "snack" for the flight, which in today's times of airline belt-tightening is what passes for the inflight meal. Removing the plastic wrapper from the tray revealed a small bag of some sort of highly-spiced cracker-like doodads and a little plastic cup whose foil top read, in big letters, "Havarti". So, basically, cheese-and-crackers, but cheese and crackers that have gone uptown.

Or so it seemed, until I actually tasted them. The cracker doodles were so awful I could barely swallow one--very, very salty, with an overwhelming layer of powdered artificial flavoring blown onto the exterior. I put them aside, thinking, "at least I can eat the havarti."

But, upon closer inspection of the fine print on the foil wrapper, I noticed it wasn't Havarti at all. It was "Pasteurized Process Cheese Spread Havarti-type Flavor." The first ingredient in the "havarti" was actually "cheddar cheese". Apparently, to make “Pasturized Process Cheese Spread” with “Havarti-like flavor”, you take plain old cheddar cheese and add to it water, cream, milk, and whey--to make it more fluid, I suppose, and better suited for packaging in a little plastic cup. Then, throw in some unspecified “natural flavor”, salt, and calcium propionate and—pow!—instant class.

Honestly, what would be so bad about some plain old crackers and cheddar cheese? Saltines would have been just fine—a little boring, maybe, but at least would have been edible. And, the most boring and washed out of supermarket cheddar cheeses would have been better than the so-called Havarti.

Why pretend that American airline travel is more elegant than it is? As Joe Bob Briggs pointed out in his classic column "Sardine Me!" , we are not willing to pay enough. So how about a good ole pack of Lance crackers instead?

At least there was Walker's shortbread in the snack pack too--wheat flour, butter, sugar, and salt. It's just as pretentious a thing to serve as the faux Havarti ("Imported from Scotland!"), but at least it tastes good.

Sunday, July 09, 2006

Ventilation

With the arrival of our second son back in March, our family has outgrown our present house, so we've got it on the market and are looking for a new, larger one. My wife has a long list of requirements for the new place--everything from the type of siding to the number of sinks in the master bath--but I have only one: the stove's exhaust fan must ventilate to the outside.

It doesn't look like we're going to be moving any time soon.

We've toured close to twenty houses, of varying sizes and styles, though all of them were built in the last 20 years. And, in every single one of them, the hood over the stove does not have a pipe that takes smoke and vapor outside. Instead, they all pass them through a thin, cheapy filter and push the air right back into the kitchen.

My current kitchen has just such a fan, and it is all but useless. Many of my favorite dishes--like braised meats and pan-seared steaks--involve an initial browning over high heat in order to get a good char on the meat. And this browning puts off a lot of smoke. So, I click the hood fan to high and it's so loud as to drown out conversation, but the smoke that it pulls into the fan is immediately spit right back out into the room, apparently unimpeded by the little charcoal filter inside. My favorite dishes, therefore, are all but guaranteed to fill the the whole house with thick greasy smoke, set off the smoke alarm, and start the baby wailing.

Perhaps, like flat-top ranges that are easy to clean but terrible to cook with, this is a symptom of how little real cooking most Americans do. Unless you are going to really crank up the stove and try to brown meat--and, honestly, how many people really do that these days?--you'd probably never even notice that the fan is ineffectual. So, why should a builder bother with the slight additional expense of running the pipe to duct the fan outside?

Because of my lack of effective kitchen ventilation, I've had to put a moratorium on creating one of my all-time favorite dishes, Pollo al Matone, which is Italian for "Chicken-Under-a-Brick" (I always call it the latter, which has such a nice ring to it.) This usually is a grilled chicken dish, in which a whole chicken is roasted over a fire with a big stone pressing down on it to flatten it out and make sure it cooks evenly. I do a modified stove-top and oven version that I borrowed from Mark Bittman's How to Cook Everything and make in a big cast iron pan.

Chicken Under a Brick

1 whole chicken

2 tsp Kosher salt

1-2 cloves minced garlic

1 Tbsp minced rosemary

olive oil

Preheat oven to 450 degrees

Prepare the chicken by removing the backbone and splitting it so it will lay flat. To do this, use a sharp knife or kitchen shears to cut along either side of the backbone from front to rear, removing it as a single 1- to 2-inch wide strip. Then, spread the chicken out flat.

In a small bowl, mix about 1 Tbsp olive oil with the salt, garlic, and rosemary, then rub the mixture all over the chicken--both the skin-side and the inside.

Heat a large cast iron skillet over medium high heat, pour in about 1 Tbps of olive oil, and add the chicken, skin-side down. Then, weight the chicken so that it is firmly and evenly compressed. I usually cover the chicken with a piece of aluminum foil (just to make clean-up easier), then place a smaller cast iron skillet on top and an antique cast-iron clothes iron that I've found at a flea market and weighs close to ten pounds. You could use a brick or a big rock as well--it just needs to be heavy enough to press the chicken nice and flat.

Cook on the stove top over medium-high heat for about 10 minutes, then move to the 450-degree oven. Allow it to roast for 15 minutes, then remove the pan, turn the chicken over, replace the weights, and put it back in the oven for another 10 minutes. (This last part can be a bit dangerous. Keep the kids out of the kitchen and use good, thick oven mitts on both hands--all that cast iron will be hot!) Before serving, pierce the thighs with a knife and be sure all the juices run clear. Remove the chicken to a platter, cut into pieces, and serve.

This requires a little heavy lifting and a lot of greasy smoke from the super-hot pans and oven, but it is very much worth it. The chicken skin will get so delightfully toasted and crispy, and the meat will be the juiciest, most flavorful you will ever have.

Maybe I'll luck up and find a house with a proper external-ducted range hood. If not, I'll just have to wait till Fall arrives and I can open all the windows and go nuts. Boy, do I ever miss chicken-under-a-brick.

Popular Posts

-

The latest episode of the Winnow is now out, and in Episode #7 Hanna and I talk dining institutions of all sorts: cookbooks by big-name...

-

I'm on the hunt for bacon. Specifically, for places in Charleston serving bacon in interesting or innovative ways, for a feature I'...

-

Actual items from the Seven Year Old's school lunch menu for the month of January: "1/3 less sugar frosted flakes": I'll ...